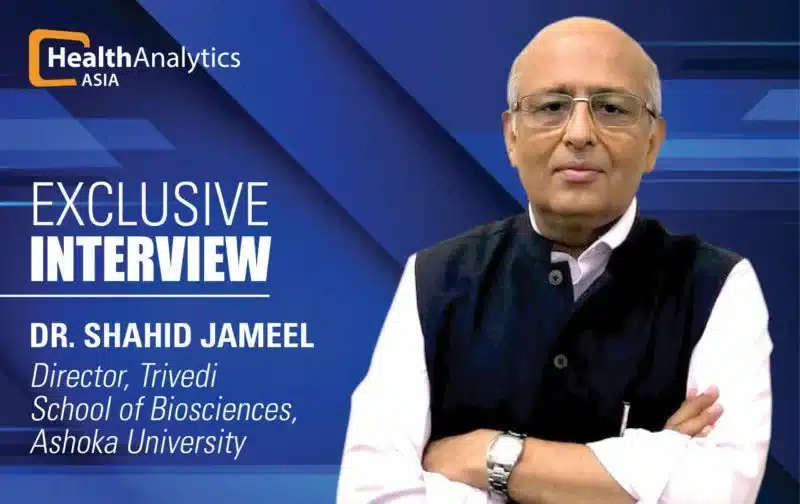

As the pandemic moves on to the stage of mass vaccinations, “Trust is,” asserts Dr. Shahid Jameel, “important for people to be mindful of what a vaccine can offer and what a vaccine can’t offer.”

On the first day of 2021, nearly half a million people were infected by COVID-19 globally, and about 10,000 lost their lives. But as the pandemic still rages on, the new year has brought hope. The world had been desperately waiting for a vaccine. We now have several. Over 40 countries have already administered millions of doses of COVID vaccines. India too has approved two vaccines for emergency public rollout. As this process unfolds, there are questions that need answering – questions about the vaccines, their approvals, the data, among other things.

To understand all the yin and yang of India’s vaccines, HealthLEADS spoke to one of India’s top virologists Dr. Shahid Jameel. Presently, Director of the Trivedi School of Biosciences at Ashoka University, he has served as the CEO of Wellcome Trust-DBT Alliance for over seven years.

Starting off with India’s COVID scenario – some states in India have seen multiple waves of infection, many haven’t. Do you think India has avoided a second wave as a nation?

India’s first wave was quite broad. The peak was not very sharp. As a result of that, I think India may not have, what we traditionally call, a second wave. This is entirely my hypothesis. But if you look at the number of people who may be infected with the virus already, based on different serosurveys and testing done by companies in the private domain, it appears that India may already have 300-400 million infected people. If that is the case, a lot of the population has already been affected, and they may have some level of immunity that would protect others from getting infected. There are also epidemiological models that predict somewhere around 30% of India’s population on average to have been infected. It explains quite nicely why India, on the whole, may not have a second wave.

The other point to consider is that in our festive season – Dussehra, Diwali, and the period in between – we also had Bihar elections. You would have seen pictures of election rallies where there was hardly anyone wearing a mask. Mask use was not very prevalent at markets in major cities. Despite that, we didn’t really see a big spike in cases. There was a little blip that came around mid-November. But we didn’t really see much beyond that. All of this suggests India is unlikely to have traditionally what is called a second wave.

With what you’ve said, and the fact that vaccines are coming, is it safe to say that we are out of the woods, that the worst is over?

The moment you put it like that people become relaxed and complacent. And experts are almost always proven wrong by diseases. The worst may be over but we are certainly not out of the woods. My advice would be for people to continue to maintain precautions. Even after we get a vaccine, it’s very important for us to continue to wear masks. And the reason for that is, the end point of vaccine testing has been efficacy against disease. No vaccine claims that it will stop transmission. While I may get a vaccine, I may still get infected, not produce disease, and spread the virus to others. So my suggestion would be that even after getting a vaccine, we should continue to wear masks.

India has approved two vaccines – Oxford & Serum Institute’s Covishield and Bharat Biotech’s Covaxin. What is your opinion on both?

My opinion is simply my opinion. Science doesn’t work on opinions or beliefs, but on evidence. And evidence comes from data.

The data says that the Serum Institute vaccine has some efficacy value, although not determined through trials in India. Even this is under some cloud because their data from (trials in) UK and Brazil looked very different from each other. In Brazil they found 62% efficacy, in the UK they found 90% efficacy. Then they realised that in the UK trial, there was an error – the first dose was only half dose. I have an objection to combining data from Brazil and the UK. The data was so different, and the trial was different because the dosing was different, so I don’t think the combination can be made. Nevertheless, even if the efficacy was, let’s say, 62%, this is an efficacy value that we know. In the case of Bharat Biotech’s Covaxin, we don’t even know the efficacy value. This vaccine is only being tested in India, and phase 3 trials are ongoing. Data is just not available. I would honestly personally like to see more data.

Questions are being asked about rushed approvals, missing data. Should the common man be worried? Or is it made out to be more than what it is?

In a sense, the common man shouldn’t be worried at this point because the common man isn’t getting the vaccine at this point. Government of India’s vaccination plan is to first vaccinate 10 million healthcare workers, and then 20 million frontline workers. Only after we are done with these 30 million, the rollout will begin for the other 270 million who constitute people above 50 years of age, and those below 50 with comorbidities. By the time that happens, we will have efficacy data for both vaccines from India. I truly believe that both these vaccines will give us reasonably good efficacy data. But this is simply my belief. I have to wait to see the data.

With this rise in questions and doubts, what do you think are the top challenges India faces – in mass vaccinating, in maintaining, perhaps even rebuilding public trust?

India faces a couple of challenges. The first challenge is going to be delivering these vaccines – to 30 million people very quickly, and then another 270 million priority group, over the year. I believe the government has made good preparations for it. There is a plan in place. There have also been dry runs.

As for building trust – it is a key to controlling disease, especially pandemics. Trust is also important for people to be mindful of what a vaccine can offer and what a vaccine can’t offer. I think the best way of securing trust is to be completely transparent and make sure that all the data is available openly.

To people who don’t do science, it appears that science has an answer for everything. Science doesn’t. Science also goes wrong. What we may have a proof for today, may be proven wrong tomorrow. It’s very important for people to understand this, and for the scientific community and the governments to emphasise this. It’s important, to tell the truth, and be honest, be upfront, be transparent. That will build trust.

The single biggest damage to the reputation of both these vaccines has come from the vaccine companies themselves. Their CEOs started trashing each other in public. The two gentlemen should have had some sense and not started their corporate wars on national television. Yes, they made up a day later and issued a joint statement. But in my view, the damage is done.

The Subject Experts Committee (SEC) met over three days during which proposals and presentations were made by both vaccine companies, after which came to the approvals. Are you satisfied with the process?

All I know is that the SEC met for three days. So apparently they spent a lot of time discussing this matter. But what data was presented to them, what was the discussion that happened, I’m not privy to that. I don’t even know who the members of that committee are. If there is a committee deciding whether I should get a vaccine or not, the least that should happen is that I should know who the members of that committee are — the names should be public. Why is there such a secrecy around the members of the SEC? Look at what the US-FDA did, when the US president was putting pressure to approve the vaccine quickly. They held an open meeting, open to anyone to attend online. All the deliberations, and everything that was said is a matter of public record. That sort of transparency builds trust. Honestly, I don’t even know what happened in those meetings so how can I even comment on whether the decision was right or wrong?

Bharat Biotech’s vaccine is a “whole virion” type vaccine while Covishield is a “recombinant viral vector”. For people receiving these shots, is this difference something to think about? Can you break this down in common parlance?

People who have to take these vaccines don’t have to worry about the differences in these vaccines. They only have to worry about how safe and how efficacious the vaccine is. But let me break down what these two vaccines are all about.

The whole virus vaccine is a very time-tested platform. In this vaccine, you take the virus, grow it up in culture in large amounts, purify it away from the cell debris, inactivate it using a chemical and then this inactivated virus is mixed with substances called adjuvants, that enhance their immune capability. One advantage of these vaccines is that since there is no live virus, they are safe. The other is that it includes all the components of the virus – all the proteins. So you raise a very broad response, instead of a response to only one protein. Multiple vaccines in use today use this platform. Bharat Biotech itself has a lot of experience in making these vaccines, and they have used it extensively.

The Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine is a viral vector vaccine that uses the chimpanzee adenovirus – a virus that causes the common cold. There are human and other animal adenoviruses also, the one used here is the chimpanzee one because chimpanzees are evolutionarily very close to humans. The efficacy of human adenovirus vector-based vaccines would be less because humans would already have immunity to human adenoviruses. The chimp adenovirus is simply used to deliver the gene for the spike protein and that gene expresses and produces the spike protein and develops antibody responses.

So the viral vector vaccine would only produce a response against spike protein, whereas the whole virus would also produce an immune response to various other proteins of the virus.

SEC recommendations repeatedly mentioned Bharat Biotech’s lack of efficacy data. It seems that only upon their claims of being more effective against potential new strains of the virus, that emergency use was authorised. What is the concept behind these claims? And how substantial are they?

What the committee may have considered is that since the Bharat Biotech vaccine is a whole virus vaccine, people who get vaccinated with it will also raise immune responses to other proteins than the spike protein. Their logic would’ve been that since mutations are being seen in the spike protein, responses against other proteins would also protect against variants. But I think this is flawed reasoning – simply because there is no data at this time whether the new variants that have emerged will escape existing vaccines. In fact, there is some evidence to the contrary. So if that was the reasoning, I don’t really buy it.

The second is that the only other protein against which you will make antibodies in the Bharat Biotech vaccine is the nucleocapsid protein – which is present inside the virus, not on the surface. The antibodies to the nucleocapsid protein will not neutralise the virus, simply because this protein is not present on the surface and antibodies cannot go inside the virus. These antibodies will also not neutralise the viruses that are infecting us because those viruses produce the nucleocapsid protein inside the cells and antibodies cannot enter cells. Having antibodies to the nucleocapsid offers no protection. From a vaccine point of view, I don’t think it gives any advantage. It’s scientifically flawed reasoning.

Covishield is the Oxford vaccine in India. But in trial registrations, the Oxford vaccine is mentioned separately and is used as a comparator agent in trials, against Covishield. How does one vaccine have two different versions?

It’s the same vaccine. It’s just that the Serum Institute is manufacturing it here in India. The seed stock for the vaccine came from AstraZeneca. The vaccine used in trials in the UK, Brazil, and South Africa, was made by AstraZeneca; the vaccine that went into trial in India was manufactured by Serum Institute. It’s the difference of manufacturers, the seed is the same.

Covishield’s phase 3 trials were registered for a period of 7 months, but data was available within 4 months. Covaxin trial durations were supposed to last even further down in time. How are trials happening so fast?

After the two doses (of the vaccine) have gone in, there is an extended period of time in which you look for adverse events. That is the entire trial period.

I think trials have been done properly. The most important thing to see in the trial is whether it has proper inclusion and exclusion criteria and I’m sure those have been followed. The other is whether the time duration between the first injection and the second injection has been followed – and I think that has been followed.

The Indian Drug Regulatory Act does not have any emergency use approval but the Drug Controller of India has the authority for accelerated approval. The US FDA and the European Medicine Agency guidelines on emergency use approval say that emergency use approval will be given only two months or 70 days, respectively after the vaccination is complete. There is a scientific reason for this — any adverse events will come within six weeks and therefore you want to wait two months before any emergency use approval.

What is paramount is that a vaccine should be safe. The vaccine may not have high efficacy, and may not provide the desired protection, but at least it should not be harmful. Safety is very important and that’s why this two-month period.

Part of the problem is whether both of these companies have completed the two months after the second injection and whether enough period has elapsed after both injections. Have two months or at least six weeks elapsed between the second injection and the data that was presented to the committee? That’s the key question and I don’t know the answer to that, because I have not seen the data.

The words used for Covaxin are “approval in clinical trial mode”. Does that make the population guinea pigs?

This word “approval in clinical trial mode” is an invention of the SEC and DCGI. No vaccines are given approval in clinical trial mode. This initially created a lot of confusion.

Clinical trial mode suggests that whoever gets the vaccine will be split into two groups – one gets the placebo group and the other gets the vaccine. The initial confusion was if people would be divided into two groups as well? They clarified that’s not the case – everyone will get the vaccine. It’s like an open trial now, not a blinded trial.

The second confusion was – for Covaxin, anyone who has prior exposure to COVID, HIV, Hepatitis B or C, will be excluded from the trial. Anybody who lives in the same house as a person exposed to the COVID virus will be excluded from the trial. The second confusion that arose is how will people be excluded? Would anyone who gets the vaccine first get tested for COVID, HIV, Hepatitis B, and Hepatitis C? Later it became clear that exclusion criteria will not be followed.

The third confusion was – everyone in a clinical trial is covered by health insurance against injury from the vaccine. Would anyone who gets the vaccine in clinical trial mode also be covered by the insurance? This was not clear at all.

These were the points of confusion and later they clarified that what they meant by “clinical trial mode” was that people who get the vaccine will be followed very closely. They will have to report every two weeks whether they have any adverse effects. They would have access to hospitals to go and get treated if they have any problems. It’s the language that made it very confusing. The DCGI, when he made this press conference, did not take any questions. It would have been far better to take questions and clarify these issues then and there.

Given that multiple vaccines are being approved — of different platforms and in different manners — do you think that it should be the choice of the recipient on the vaccine they get?

It depends on who is getting vaccinated and when. Let’s take the case of India – if you fall within the 30 million healthcare or frontline workers, the government is going to give you the vaccine that they’re able to procure to give it for free. There you won’t have a choice as to which vaccine you get.

Your choice may be to say, “I don’t want this vaccine,” and people should be able to exercise that choice. Just because you’re a healthcare or frontline worker, it should not be made mandatory. But frontline workers would also be more prone to infection and transmitting the virus due to the nature of their work, and I believe they should take the vaccine. People should be educated and convinced to take the vaccine instead of making it mandatory. Because the moment you make it mandatory, it raises all kinds of other questions.

However, towards the end of this year or maybe next year, when vaccines might be available either through the government distribution system or in the open market, then of course it’s your choice. Then the market economics will decide. If you have the money to go and get a Moderna vaccine from the chemist shop and get yourself vaccinated, you could do that. If you want to still get the Serum Institute or the Bharat Biotech vaccine through the government system, you could get that.

Do you see that open market system happening in India?

Eventually, it will have to be a public-private partnership. I don’t think the government can afford to vaccinate everyone who needs to be vaccinated, free of cost. I think it will happen even with the 270 million people who are a priority. The government has not said that it’s going to make vaccines freely available to this group. They have so far only said that vaccines will be freely available to the 30 million people on priority. So for the 270 million, you may also see a public-private distribution model.

Taking a step back, what are the lessons that you think global health programs and vaccine development programs have learned?

The top lesson is that science has been able to defeat this pandemic. So believe in science, believe in facts – don’t believe in all the other chatter that you hear. There is a need to strengthen both science and the scientific process, and for people to understand what it is all about. It’s the doctors and the scientists who have really gotten us out of this mess.

Remember when the pandemic started, the mortality rate was somewhere around 9 or 10 percent globally. Today it is about 2.5%. The virus hasn’t changed. We have learned how to deal with it, how to treat it in clinics, in hospitals. Doctors are sharing information and they are the real heroes of this. Information is being made publicly available in real-time and that is what has made the difference. People are sharing clinical protocols – what works, what doesn’t. That is saving lives. So it’s very important for information to be available openly and for us to believe in the method of science.

As a country, we need to strengthen our public health system down to primary healthcare centres. Primary healthcare centres are the first to look at infections and disease and catch it before it becomes big. They need to be strengthened a lot.

The third lesson, globally, is that viruses will keep emerging. This is not the last one to have emerged. How are we preparing ourselves for the next one? There are certain positives that have come through in COVID times. To my mind, the biggest positive is the speed at which vaccines have been developed. The mRNA technologies are turning out to be really quite successful. This is the future of vaccinology. Remember the Moderna vaccine went from sequence to start of Phase 1 human trial in 63 days. We have the capacity to cut it down. If we’re able to do that and we are able to have a large distributed system of making vaccines, then we will be able to control future outbreaks before they cause too much death and destruction.

We (also) have to address the root cause of these outbreaks and the emergence of pandemic viruses. The root cause is how we are playing with our environment. All of these viruses are jumping from wild animals into humans. We have to limit the interface between wild animals and humans, which means that we have to stop cutting down forests. We are all talking about vaccines, but go back and see how it came by. It did come from a wet market in China, but from where did it come to the wet market? It came from the forest. Let us stop the destruction of our environment, that’s the root cause of all this.

COVID-19 research and vaccine development has been unprecedented. How do you see this influencing existing health problems, like HIV & Hepatitis?

With every disease, every infection, you learn some lessons. And I think one lesson that we have learnt is how important it is in disease research to share knowledge openly. The funny thing is that research is largely funded by taxpayers’ money through national grants all over the world. Research is done by people who get their salaries largely from public money. Research papers are reviewed by people who get no compensation for reviewing papers. But publishing companies charge you and me to read those papers. It’s a very funny model. This has to stop, it’s a completely wrong model. Nowhere will you see this kind of model. If there’s one lesson we’ve learnt through this pandemic, it’s that open access to information is crucial in dealing with disasters.

All COVID research was open access. All the journals that hide their other research behind paywalls, made COVID research open access. And that’s why you see such fast progress in vaccine development, in treatment protocols, in everything.

As a virologist, and one of the leading voices, what has been your biggest learning during the pandemic?

There are time-tested ways to protect ourselves, protect each other. We must continue to do that. Each of us is responsible for limiting transmission of the virus, (and in doing so) limit mutations in the virus. It is no surprise that viral mutants are emerging in places like the UK and South Africa, where people are running around without wearing masks. It is possible that we may also have a variant independently developed in India that we don’t know about. Each one of us, as citizens of the world, owe a responsibility to each other, to society. Governments can only do so much. At least we can wear a mask, we can avoid crowded places. The government should make a policy that makes it easy to do that. I do understand that for somebody who doesn’t know where the next meal is coming from, wearing a mask is not going to be the topmost priority. All of us also owe personal responsibility. And to me, that’s the biggest lesson, the biggest learning. Also, a lot of gratitude to all the people who really worked day and night to ensure that everyone else is safe – our doctors, healthcare workers, security forces, sanitation workers, everyone. Big gratitude to all of them for what they have done.