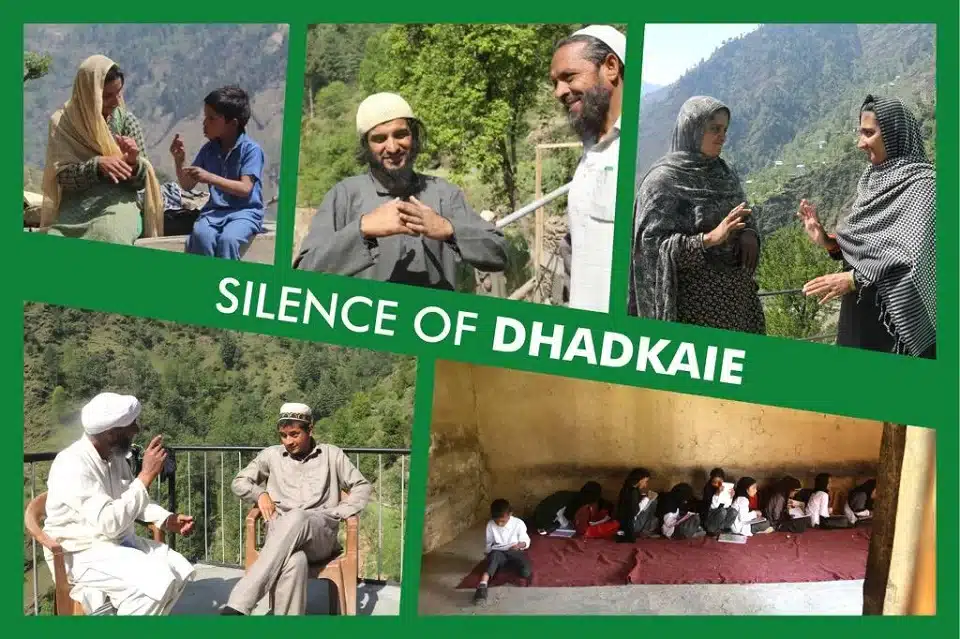

The mountain village in Jammu and Kashmir is believed to have the world’s highest prevalence of deaf and mute

Located on a mountain slope in the Doda district of Jammu and Kashmir, Dhadkaie is locally known as a “silent village.” This is for a reason. The village is home to 55 families with deaf and mute children, out of a total of 300, making it the only place in the world with the highest prevalence of this condition.

The deaf and mute work in fields and rear cattle like any other normal person but they rarely venture outside the village, preferring to stay within their social circles.

Doctors have identified Otoferlin as the gene responsible for the non-syndromic deaf-mutism. They also believe the cases are caused by generations of inter-marriage in the community.

In Dhadkaie, most deaf and mute women are unmarried and stay with their parents, battling fear and stigma

Gulab-ud-Din Choudhary, 55, could not marry his three deaf and mute sisters who are in their 40s.

“No one wants to bring this defective gene into their family. Why will someone risk having a deaf and mute child?” Choudhary asked. “Initially, we married some deaf and mute girls but most of them returned to their parents after facing harassment from in-laws.”

The authorities are now encouraging the residents to break their isolation and search for partners further afield, but to no avail.

Suspicious of outsiders

The villagers are skeptical of people with cameras and taking notes presuming them to be doctors. They don’t want to cooperate, saying they have given enough blood for samples.

A small health centre is without a doctor and drinking water is drawn from springs.

The villagers largely depend on agriculture, livestock and daily wage labour for their livelihood.

A long uphill trek takes a person to Dadkhai but it is a routine for the villagers.

The closed and quiet community has never committed any crime, local police records reveal.

No hope

Choudhary Mohammad Hanief’s three-storey house sits prominently in the centre of the village. In politics for a long time and heading the Block Development Council of the region, he has been inviting doctors from across Jammu and Kashmir to find some cure for the disease. But now he has also given up.

Hanief’s own children, Shabir Ahmad, 34, and Aftab Ahmad, 18, are also deaf and mute.

“They are master masons but they cannot talk or listen,” said Hanief who dons a white turban and sports a long beard.

His children also don’t like doctors. “Over the years teams of doctors visited the village taking blood samples of our children and then we didn’t hear anything from them,” Hanief said. “No solution was found to stop the spread of this disease to our future generation. We didn’t even get a special school for these children in the village.”

Gene out of the bottle

Official data reveals at least 83 people, mostly females, are affected by the defective gene.

The deaf and mute case was first reported in 1901 when Meran Baksh was born to a family who migrated to the village from nearby Jammu district. He was alive until the early 90s.

Genetic mapping has, however, shown that more than one lineage is responsible for the spread of the disease rather than spreading solely from Baksh, as the villagers had suspected.

Doctors reckon the disease received social acceptance in Dhadkaie and people with similar genetic disorders migrated to the village, resulting in a rise in cases.

Hanief married at a very young age to his distant cousin. There was no one in their families with hearing and speech impairment.

“I never thought my child would be deaf and mute,” he said. “I was fearful though. Everyone in this village is.”

Hanief said bringing up disabled children is tough. “You have to keep track of them. They have no one except you,” he said. “You have to know their language and as a parent, you die every day thinking what will happen to them after your death.”.

When Shabir was 12 Hanif took him to Jammu for a medical check-up. The boy gave slip to him and disappeared. He found him six days later on a road to Punjab.

“I still cry thinking what he might have done during those six days and nights,” Hanief said, his eyes welling up.

Bottling the gene

In 2014, an Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) team screened 2,473 villagers and found 33 children below 10 years suffering from hearing impairment, while 39 adults turned out to be deaf and dumb.

Dr Sunil Kumar Raina, the principal investigator, who led the team of researchers, said the village has the “world’s highest prevalence of non-syndromic deaf mutism”.

Genetic testing, according to the doctor, showed autosomal recessive mutation among the people, causing a high prevalence of cases linked to consanguineous marriages.

To change the village’s fate, doctors are now encouraging residents to break their isolation and search for partners outside their families.

There’s even talk of introducing a colour coding scheme for marriages for affected individuals, to avoid the manifestation of the Otoferlin gene. If implemented, it is expected to banish deaf-mutism from Dhadkaie.

According to the scheme, marriage within the community should be on the basis of colour-coded cards: for example, one who has 25 percent of the disorder should marry someone who has 50 percent, but the one with 50 percent disorder should not marry the other with the same percentage of disorder. Since the manifest phenotypes will identify themselves easily, the fact whether one is a carrier of disease or not should be the determining factor for all marriages in future.

Listening to the experts, several families either married their children outside the village or migrated to the neighbouring state of Punjab to control the spread of the disease.

Deep skepticism

The villagers are not convinced that the colour-coding works.

“It has not helped. Even when we have married outside the village, the couples have given birth to a deaf and mute child,” said a retired teacher Fazal-ud-Din, whose son and daughter are deaf and mute.

Having deaf and dumb children at home means a mixed bag of troubles for the parents as they can’t leave them alone.

They can’t communicate with the doctors about their diseases, can’t sleep alone in the room, or go outside the village on an errand.

But the villagers can’t do much about it. Many of them have sought refuge in fatalism, believing they are cursed.

“Yes, we are under a curse,” said Hanief. “And we want God to forgive us our sins. This alone will deliver us from this blight.”