Once applauded for its low coronavirus incidence rate and mortality, Japan has been recording an exponential rise in new cases per day since June-end. The government’s focus on stimulating the economy is posing new public health challenges.

In May 2020, when most countries were dealing with thousands of COVID-19 cases, Japan was applauded for its low coronavirus incidence rate and mortality. Japan’s Finance Minister Taro Aso famously attributed this to ‘mindo’- a term denoting Japanese cultural and intellectual superiority.

However, by June-end, Japan started to record an exponential rise in new cases per day and has shown no sign of slowing down since. With a record-high of 1,991 new cases being reported on August 3, Japan presents a peculiar case of the battle against the coronavirus.

Questions galore

In the beginning, Japan’s low incidence of COVID-19 was particularly surprising, since it houses the highest proportion of elderly citizens in the world. Also, Japan had a relatively low testing rate at 0.16 per thousand people (which is under half the testing rate of India at 0.41). Yet it kept its international borders open (barring entry from select countries) since the beginning of the pandemic. Furthermore, Japan’s government has not imposed a lockdown till date.

On April 15, a state of emergency was declared and people were asked to avoid crowded areas, restaurants, and non-essential travel. At the time, Japan’s first wave was hitting its peak, with a maximum of 743 new cases being observed on April 12. On May 25, Japan lifted its state of emergency: its active case count was dwindling and in the double digits, and remained so for the next month.

Japan has two alert systems for COVID-19 implemented in each of its regions: the infection status (indicating the spread of the disease) and the medical service system status (measuring how close to capacity the country’s medical system is at the time). Currently, Tokyo’s infection status is at the 4th and highest possible level, which – according to the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Health and Welfare Bureau – roughly translates to the “infection is spreading”. The medical system status is on a mid-level alert, which translates to “the system needs to be strengthened in order to deal with predicted demand”.

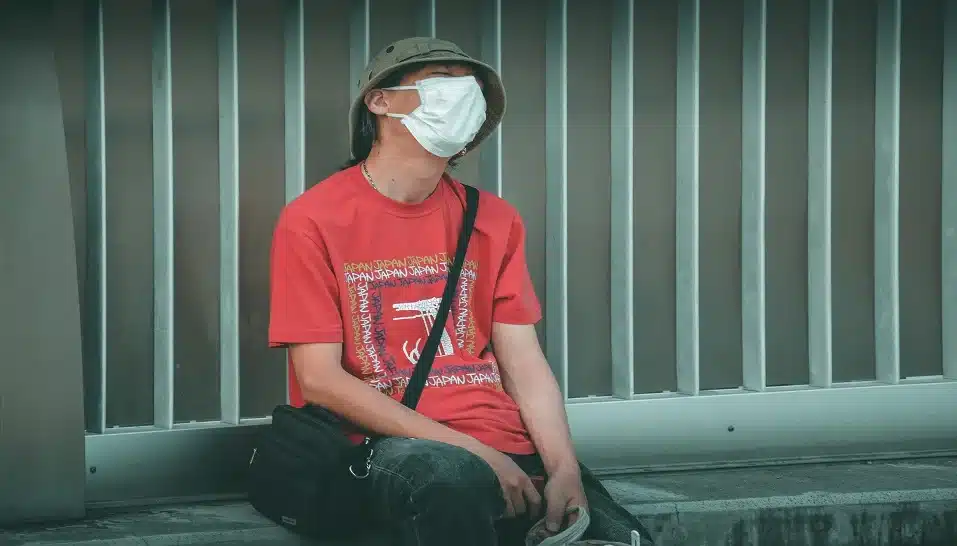

Despite these alerts, the economy has been reopened. In June and July, locations of mass gatherings in Tokyo resumed operations, including Disneyland, Tokyo Tower, and Tokyo National Museum. This could likely have contributed to the rise in cases in the densely populated Kanto region (where Tokyo is located). In April too, when Japan had its initial outbreak, nightclubs and restaurants were responsible for the largest clusters in Tokyo, including the famous Kabukicho district, which is known for its clubs, bars, and red-light districts. Given that young people frequent nightlife hubs and public attractions more than the elderly, it’s no surprise that the majority of COVID-19 cases come from the 20-40 age group.

Considering that coronavirus has more detrimental effects on the elderly, one might think that the youth being most affected by the virus is not a cause for concern. However, in countries across the globe, particularly the United States, a pattern of young people passing the virus on to the elderly over time has been observed, and experts warn that Japan’s COVID-19 patient population will experience this age demographic shift too.

Too much travel?

Had the COVID-19 pandemic not struck, Tokyo would have been hosting the 2020 Summer Olympics. While the games were initially set to begin on July 23, they have now been postponed to 2021. In its absence, the Japanese government has decided to promote tourism within the country through the Go-To Travel campaign. This campaign – intended to boost the economy – offers subsidies up to 50 percent of all costs for domestic travel in Japan. These costs include hotels, transportation, restaurants, and tourist attractions.

While the policy offers relief to local businesses in a time of economic hardship and slowdown, from a public health perspective, this policy not only allows but encourages travel from regions of higher infection to regions of lower infection. While Tokyo has been excluded from this campaign due to its state of emergency, other severely-affected regions including Kansai, Kyushi, and Chubu – with over two thousand active COVID-19 cases each – are part of the campaign.

The government’s current strategy is to monitor the situation through tracking and testing, while also focusing on stimulating the economy. This approach has received severe criticism from the public. In a recent poll conducted by the Japan News Network, over 60 percent of respondents were dissatisfied with the Japanese government’s response to the pandemic. The popular sentiment is that stricter preventative measures are needed to deal with the current crisis.