Ranbaxy was like a rising star of the boom in global generic medicines. Behind it was a story of a man who came to Delhi from Rawalpindi in Pakistan after partition to build one of India’s largest Indian pharmaceutical company. What brought about the fall of Ranbaxy and its owners—Malvinder and Shivinder Singh who are now facing probes and court cases? Was Ranbaxy an industry outlier, or the tip of the iceberg? Are low-quality standards pervading the generic drug industry? Are generic drugs safe?

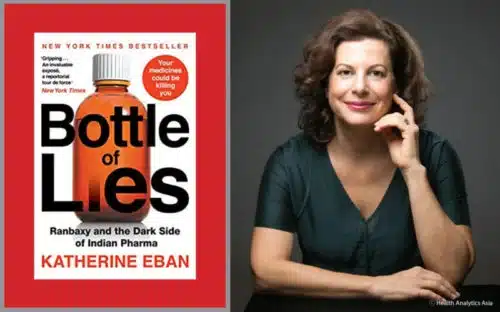

Over ten years, American investigative journalist Katherine Eban investigated and uncovered nothing less than a public health crisis.

Comprehensively and for the first time, Katherine tells one of the biggest exposés of the generic drug industry in her book Bottle of Lies: The Inside Story of the Generic Drug Boom. “Generic drugs are essential to global public health, and are a godsend when made properly, Katherine said in an email interview with Health Analytics Asia. “But the book also makes clear that patients have been harmed by the rampant fraud and low-quality standards pervading the generic drug industry.”

In the interview, Katherine discusses her findings and how regulators need to step up to protect patients and what motivated her to write the book. Edited excerpts from an interview with Katherine Eban:

1. Your book is a damning indictment of generic drug manufacturers in India and China, with countless examples of fraud and corruption. In the course of your investigation, what was the most shocking revelation you came across?

To me, the most shocking revelations were the extent and depth of the fraud. For example, I described one Indian plant, run by Akorn India Pvt., where an FDA investigator went to the microbiology laboratory and found the facility’s paperwork for its sterility testing in perfect order: microbial limits testing, bacterial endotoxins, all the samples with perfect results. Yet the samples didn’t exist. They were testing nothing. The entire laboratory was a fake. This is really a shock.

If you’re operating a sterile manufacturing plant, that kind of testing is a bedrock requirement to ensure that your products are free of microbial contamination. If you are blatantly falsifying test data to prove your plant is sterile, what won’t you fake? I quote one former Ranbaxy executive in the book saying, “…once you get to the point where you actually wholesale make up data points, hundreds and thousands… of data points, what’s to keep you from doing anything?”

2. You are making a point in your book that generic drugs are poisoning us. What are the key concerns with generic drugs?

My book lays out two major public-health concerns with generic drugs. One is that due to endemic fraud in the manufacturing plants that are making the world’s generic drugs, largely in India and China, medicine with toxic impurities, unapproved ingredients and dangerous particulates, as well as drugs that are not bioequivalent to the brand versions they purport to copy, have reached patients in the U.S. and around the world.

The book also exposes how generic drug companies routinely make drugs of differing quality, depending on the vigilance of regulators in the markets to which they’re exporting. They often make their worst drugs – with the lowest-quality ingredients and the most manufacturing shortcuts – for the least regulated markets.

This practice is so prevalent, it has a name: dual-track production. The result is that patients in developing, or less regulated markets, who are most dependent on low-cost medicine, are getting the worst versions. Doctors in some African countries told me they must double or triple doses to try and get a therapeutic effect. I should also say, the language about generic drugs poisoning us is not actually claimed in the book. The New York Times used it as a headline for its (very positive) review of Bottle of Lies. Other outlets picked up that language.

The book makes clear that generic drugs are essential to global public health, and are a godsend when made properly. But the book also makes clear that patients have been harmed by the rampant fraud and low-quality standards pervading the generic drug industry. The book features several heart transplant patients at an Ohio medical centre, who suffered organ rejection after taking a generic immunosuppressant manufactured by an Indian drugmaker. It also describes a boy suffering from a bacterial infection who died at a hospital in Kampala, Uganda, after being given a Chinese-made antibiotic that contained less than half the active drug ingredient stated on the label.

3. You spent almost five years writing, reporting, collecting documents and travelling for this book. What motivated you to write the book?

My reporting on the generic drug industry actually began a decade ago, when I was contacted by the host of a U.S. radio show, The People’s Pharmacy. The host, Joe Graedon, said that patients were contacting him with complaints about side effects from their generic drugs.

He suggested I look into the question of what is wrong with the drugs. It quickly became apparent to me that just documenting patient concerns would not get me very far in answering that question. I realised the answers most likely lay in the manufacturing plants and boardrooms of the companies making our drugs – which meant in India and China. Over the next five years, I wrote a series of articles about generics, which culminated in a 10,000-word article for Fortune Magazine about India’s largest drug company, Ranbaxy.

The article told the story of a whistleblower, Dinesh Thakur, who’d alleged to the FDA that the company had submitted fake data to regulators in countries around the world, in order to gain market approval for its drugs. But that article left me with an unanswered question: was Ranbaxy an industry outlier, or the tip of the iceberg? That was the investigative question that carried me into the book project, which I worked on from 2014 on.

4. What was the biggest challenge in writing the book?

The biggest challenge was: how was I, as an independent U.S.-based journalist — without a newsroom, a team of colleagues, or other resources at my disposal — going to be able to penetrate an industry, and companies, that were based on another continent? The difficulties of a global investigative project were unrelenting.

The challenges along the way stemmed from that initial one. Warned of safety risks in India, I tried to meet sources only in public places. In China, I was followed by government security officials, who in one instance commandeered the home screen of my I-phone, to send me a picture of a security official seated in my hotel lobby, holding up an English language newspaper. The message was clear: I was being watched. I met a reluctant whistleblower from one company in a bar in Mexico City, and he ultimately gave me important documents. The reporting was like that: global in scope, painstaking, and trying to convince one source at a time to cooperate and share information. In the runup to publication, the threats were legal ones, from companies who were trying to intimidate me and my American publisher into not including all the information we had. But in the end, I am happy to say, the book and the truth won out.

5. Your book reveals the risks to the health of the American consumer. What’s at stake for Asian patients, particularly those from Indian and Chinese patients where the generic drug market is huge?

As I’d mentioned above, the book exposes what is called dual-track production: that generic drug companies routinely make drugs of lower quality for less regulated markets. Those markets include India and Southeast Asia, where regulation is lax. Patients there may be getting generics with substandard active and inactive ingredients, that are not clinically equivalent to the brand, have toxic impurities or foreign matter in them, such as metallic and glass fragments. The consequences can be life-threatening.

6. The FDA says factories in India and China – two countries with the most drug factories outside the U.S. – have lower scores because it reflects more robust inspections that have uncovered problems. Do you agree with this statement?

I do not agree. To the contrary, while the FDA routinely conducts unannounced inspections in the U.S., its inspections in India and China are largely pre-announced. The weeks of advanced notice give manufacturing plants ample time to clean up the premises and “stage inspections,” as one of my sources put it. The fact that the FDA is still finding problems, despite that advanced notice, reflects deeper problems, in my view. Those problems include persistent ongoing issues with data integrity, which is crucial to good manufacturing.

7. Why are most of the generic medicines sold in the U.S. manufactured mostly in India and China?

The transition to an offshore drug supply has been decades in the making. But essentially with a drive for lower-cost drugs, manufacturing has moved to markets with lower operating costs, cheaper labour and cheaper supplies. As well, drug-makers in India and China have pushed to enter the U.S. pharmaceutical market, which is the world’s largest and most profitable. As a result, the U.S. is dependent on India and China for its medicine.

8. What do you say to those in Indian Big Pharma industry who claim that your book has unfairly targeted the Indian pharmaceutical industry while being soft and letting go off a major chunk of industries belonging to other parts of the world involved in cases of similar offence, if not more?

As an investigative journalist, I have broken all kinds of stories in the pharmaceutical sector, including about brand-name abuses and American companies. But for this project, which was a specific look at the generic-drug industry, I followed the story, the whistle-blowers, and the documents where they led – and in large part, they led to the doorsteps of Indian companies.

Read more about Katherine Eban’s book in our news section.

Add Comment