Howard Larkin in his latest article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), suggests six-point strategy to address the issue

On July 21, public health officials announced a case of paralytic polio in a young adult in Rockland County, northwest of New York City, the first reported instance of polio in the US since 2013.

New York State Health Commissioner Mary Bassett warned that the confirmed polio case in an unvaccinated adult and the detection of the virus in sewage could indicate a larger outbreak is underway.

“Based on earlier polio outbreaks, New Yorkers should know that for every one case of paralytic polio observed, there may be hundreds of other people infected,” Bassett said.

State health officials are urgently calling for people who are unvaccinated to receive their shots as soon as possible.

New York state health officials later confirmed an unvaccinated adult in Rockland County had contracted polio and was hospitalized with paralysis. Subsequently, health officials found three positive polio samples in Rockland County wastewater and four positive samples in the sewage of the adjacent Orange County.

Howard Larkin in his latest article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), suggests a six-point strategy to address the issue.

Understand the vaccines

Today, two types of polio vaccines are in use around the world. Since 2000, the US has exclusively administered Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine (IPV), which is 99 percent effective after the recommended three doses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The IPV uses killed wild-type poliovirus to induce what’s believed to be a lifelong immunity in the bloodstream. Because it is inactivated, IPV cannot cause poliovirus infection.

Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV), which previously was used in the US and is still administered in many other countries, is about 95 percent effective after 3 doses, the CDC noted. It uses a weakened poliovirus strain to induce immunity in the digestive tract and is also thought to provide lifelong protection. In rare instances, the weakened virus in OPV regains its ability to infect the nervous system. This results in symptomatic polio in about one in three million vaccinees, William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine and health policy at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, said in an interview. The reverted virus also is excreted and passed on from person to person, which likely was the source of the Rockland County paralytic polio case, he added.

Be Aware of Local Conditions

Although poliovirus infections in the US currently are rare and have not been identified outside New York State, risk factors vary regionally. So it’s prudent to be aware of any local risk or sign of the disease.

State and local health agencies also work with the CDC to conduct wastewater surveillance for certain pathogens, such as SARS-CoV-2. Wastewater sampling for poliovirus was initiated in New York after the paralytic case was reported.

Although wastewater surveillance is helpful, it may be incomplete and “given the ease of travel, any area may be at risk,” Jesse Hackell, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Care, said during an interview.

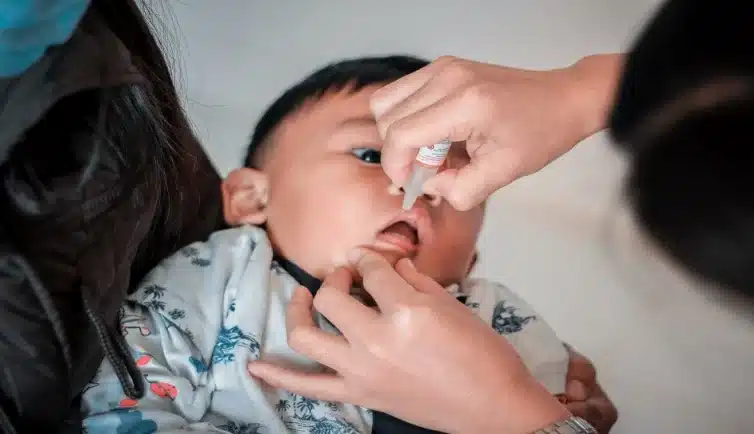

Get Patients Vaccinated

In addition to reviewing vaccine histories during visits, routine screening of patient records for polio vaccinations and contacting patients is recommended. State immunization information systems and school records are sources of vaccination records. These systems consolidate vaccination data regardless of where the doses were administered.

It’s a safe bet that anyone who went to public schools in the US in the past 70 years has been vaccinated. But if there is any question about this, offering the polio vaccine—either as a booster or a full 3-dose course—is a low-risk way to make sure patients are protected.

“When in doubt, vaccinate,” goes the refrain.

For patients who are not vaccinated or are incompletely vaccinated, a first dose should be given immediately, if possible.

Consider Booster Doses

The CDC recommends one lifetime booster shot for adults who have had three doses of IPV and are at high risk of polio exposure. This includes people who are traveling to areas where the virus is epidemic or endemic, laboratory technicians who handle poliovirus specimens, and health care workers and others caring for infected people. Healthcare workers who administer vaccines are not at higher risk.

Address Vaccine Hesitancy

With vaccine hesitancy on the rise, addressing it is essential to protect against polio and other vaccine-preventable diseases. An individual’s reason for hesitancy and the strength of his resistance varies and must be addressed case-by-case. Some people believe vaccines are no longer necessary, while others lack trust in the healthcare system. Some merely have concerns about vaccines and can be persuaded, while others are adamantly opposed to them. Others will allow vaccinations required for school while refusing others.

Know the Workup

Diagnosing poliovirus infection is complicated because the majority of people who are infected never develop symptoms. Those who do mostly have nonspecific viral symptoms such as fever, sore throat, tiredness, headache, nausea, and stomach pain. Clinical screening involves testing a stool or oropharyngeal sample for enterovirus. Confirming poliovirus infection involves collecting stool samples over two days and sending them to health department and CDC laboratories. This is complicated, expensive, and impractical for a disease that is quite rare.

Even so, screening some patients with nonspecific viral symptoms may be warranted in areas with known community spread of poliovirus.