Amid the COVID-19 outbreak, Dr. Sarthak Das, CEO of APLMA is optimistic about achieving zero malaria across the Asia Pacific by 2030. Malaria is one of the oldest and deadliest diseases of humankind. It has plagued the world for centuries. But there seems to be some hope to defeat it in Asia as the region has been at the forefront of the global decline of 60% since 2000.

In an exclusive interview with HealthLEADS, Dr. Das underlines the critical importance of sustaining efforts to prevent, detect and treat malaria which remains a significant threat to millions of people across the world.

For malaria-affected countries, COVID-19 represents a double threat. But, amid uncertainty hovering over how much damage the outbreak of COVID-19 will have on the ongoing fight against malaria, Dr. Sarthak Das, CEO of Asia Pacific Leaders Malaria Alliance (APLMA) chooses to emphasise the positive.

APLMA is an influential coalition of Heads of State from 22 countries in the Asia Pacific committed to eliminating malaria by 2030. There were an estimated 220 million cases of malaria in 2018, and about 435,000 deaths from the disease, according to the latest data available with the WHO. Children aged under 5 years are the most vulnerable group affected by malaria; in 2018, they accounted for 67% (272 000) of all malaria deaths worldwide.

“For malaria elimination in the near term, APLMA’s biggest challenge is likely COVID-19; paradoxically, the pandemic may also be an opportunity to harness momentum towards malaria elimination,” said Dr. Das.

Having worked as a public health scientist, development practitioner, and global health policy advisor, Dr. Das joins APLMA from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health where he holds appointments as Research Scientist in the Dean’s Office & Department of Health Policy and Management, and as Senior Advisor for Research Translation & Global Health Policy at the Harvard Global Health Institute.

Prior to joining APLMA, Dr. Das has served as Country Director and Regional Director Southeast Asia-Pacific for the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI). Also, he has worked as Chief of Policy and Public Sector Partnerships for Partners in Health (PIH) where he was also engaged in the West African Ebola outbreak of 2014.

Even though pieces of evidence from the 2015 Ebola epidemic in West Africa suggest that COVID-19 could derail progress on malaria elimination, this outbreak, Dr. Das believes, is clearly a different situation. “Countries in Asia have been showing the US and Europe what a pandemic preparedness in action can look like so, I am optimistic,” he adds.

Further, the progress made in the eradication of malaria from the Asia Pacific region in the last two decades has been remarkable. The region reported a global decline of 60 percent cases since 2000. While the Maldives and Sri Lanka have been certified malaria-free by the WHO, Timor-Leste and Bhutan are close to the elimination target in Asia, according to the World Malaria Report 2018.

India too reported the largest reduction in malaria cases in 2018, half as compared with 2017.

As the world observes Malaria Day on April 25 and global organisations revive their goals to control and ultimately end malaria, HealthLEADS interacts with Dr. Sarthak Das, the newly-appointed CEO of APLMA.

In an exclusive interview, Dr. Das shares the roadmap, the role of national governments and progress made so far in malaria elimination in the region and he identifies three major challenges for malaria elimination in India.

Edited excerpts from an interview:

As you take a leadership position at APLMA, what regional and national challenges and opportunities do you foresee to eliminate malaria in the Asia Pacific Region?

Firstly, let me say how honored and humbled I am to have the opportunity to serve in this role. I have lived in India, Cambodia, Papua New Guinea and have had the privilege to work in many parts of the Asia Pacific; I am eager to return. I would be remiss if I did not start with our present situation. For malaria elimination in the near term, APLMA’s biggest challenge is likely COVID-19; paradoxically, the pandemic may also be an opportunity to harness momentum towards malaria elimination and indeed our collective endeavor of developing quality health systems.

The breadth of the pandemic’s impact remains unknown in high-income countries, to say nothing of how this will unfold in resource-limited settings. What we can be certain of is that ripple effects will reverberate throughout our work in malaria and indeed global health and development for some time.

The immediate challenge for APLMA will be how we support our partner ministries, governments, and national malaria programs to navigate the balance between pandemic response and sustaining the progress made in malaria. Indeed, so many countries in the region, particularly those with more limited resources, will need to deploy available material and human resources to containment; and though while we hope containment is successful, preparation must be made for mitigation. So, I think it is important to start with that realism, as of now.

I was part of the response to the West Africa Ebola outbreak in 2014-15. We witnessed first-hand in Liberia and Sierra Leone the spillover effects on already fragile health systems on maternal and child health, TB, HIV, and Malaria programs.

One model suggested that there were 3.5 million additional malaria cases and 10,900 additional deaths from malaria across Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia as a result.

This is clearly a very different situation; countries in Asia have been showing the US and Europe what a pandemic preparedness in action can look like so I remain optimistic that worse cases can be avoided in terms of COVID 19.

If there is any silver lining, it is that COVID 19’s impact on global health will, hopefully, lead to an even greater emphasis on building the very parts of quality public health platforms that can help us accelerate malaria elimination.

Surveillance, diagnostics, sharing of data, and cross border regional collaboration is critical to malaria elimination and indeed to countering future infectious threats. The move towards malaria elimination will further strengthen such systems and reduce the challenges of allocating scarce resources. Once through the acute phase of this pandemic, as a community focused on malaria, we may even be better poised to find and articulate these synergies nationally and regionally.

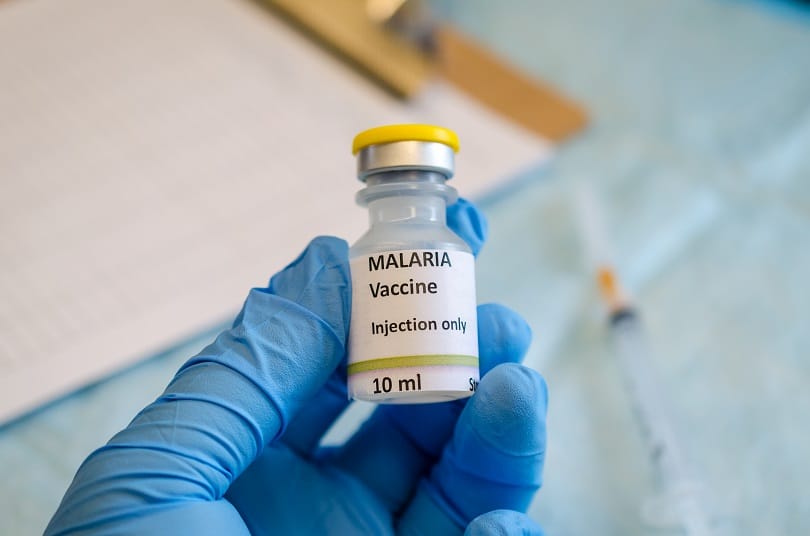

There have been reports that an anti-malarial drug is being tested for efficacy against COVID-19. How effective are anti-malarial drugs when it comes to combating COVID-19?

Recently, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the United States approved Hydroxychloroquine and Chloroquine, both drugs used in malaria, for the treatment of COVID-19 in adults and adolescents, even though there is scant empirical evidence of their efficacy for that purpose.

What is known, however, is that the drugs are relatively safe when used as they have been previously intended, information that is yet unknown is for the host of new therapeutics being investigated to treat COVID-19.

The context of this surprising approval, of course, is the overwhelming need for any treatments to improve the disease course of the tidal wave of people suffering from COVID-19. This urgent need, paired with the historical experience with these drugs in malaria and other conditions, seems to be lifting the confidence of the FDA, despite conflicting results from studies in multiple countries, all of which had small sample sizes that did not use the methods of the gold standard of research, the randomised controlled trial. Within a few months, we will learn the results of an RCT evaluation whether these malaria drugs prevent infection with COVID-19. Whether used for short term treatment of COVID-19 or as prophylaxis for those exposed to it, there are potentially serious side effects, misuse of the drugs and supply chain problems that could arise. These are issues we should all be watching carefully.

APLMA has a mission to eliminate malaria across the Asia Pacific by 2030? Is this achievable goal and what role should national governments play?

With an intensive focus over the next decade alongside coordinated attention to the right priorities, elimination in the Asia Pacific is within reach by 2030. On the whole, progress made in the past two decades has been remarkable. The Asia Pacific has been at the forefront of the global decline of 60 percent since 2000. National governments and their malaria programs need to continue to provide steadfast leadership to bi-lateral and multi-lateral partners, donors, civil society and researchers. The best partnerships are those where a foundation of trust is built upon a mutual understanding where partners are there to help governments reach their strategic objectives in health through approaches that suit their context.

The critical advantage in the Asia Pacific is the leadership on malaria that has already been shown– from the level of heads of state through national malaria programs through sub-national collaborations, the commitment to action and to directing partners is evidenced in the sharing of country-level progress towards elimination and active collaboration across borders.

Continued, sustained leadership on malaria is the greatest contribution national governments can play as it aligns the donor-partner community, provides direction and fosters the momentum needed towards elimination.

What is the roadmap to eliminate malaria completely from all the countries in the Asia Pacific by 2030?

The roadmap to malaria elimination both begins and ends with a careful examination of the data to (re) establish an intensive focus on the most challenging places in the region. While ensuring that countries such as Sri Lanka can sustain their progress is vital, we must vigorously respond to the areas where incidence is high.

Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Odisha, India, and other tribal states, as well as Cambodia all, warrant special attention. Sustained capacity building in program management at the District level is the most critical component to the achievement of elimination. Tailored, subnational efforts that prioritize District level capacity building in data analysis linked to technology and the most effective surveillance systems, including those that employ molecular epidemiological methods will be of great benefit.

Alongside this, we must bring to bear the best in evidence-based practice related to diagnostics, drugs and vector control and ensure that we enable the creation of the best package for each context. To be effective in this regard, it may be helpful to divide the next ten years into two distinct five-year phases, with an intensive focus in Phase I 2020-2025 in the most challenging contexts mentioned earlier.

Finally, we have to be relentless in sharing not only the challenges but also the progress at National and Regional levels so that we can advocate for further support not only from bi and multilateral sources but also the private sector and national budgets themselves. Success will create momentum, especially in tough places.

Speaking of innovation and applying different approaches to fighting malaria, what new tools could we expect in the coming years?

Among the most exciting new tools are emergent technology and data management within surveillance- both in terms of geospatial and genomic. The most effective tools in this regard will be the ones that can find a way for governments to use, particularly at sub-national levels.

How can we help District leaders and National control programs aggregate, analyse, and then act on these data? What are the ways these technologies can be deployed in more difficult places?

On the diagnostic side, new more sensitive, field-friendly rapid diagnostic tests to detect non-falciparum species and more sensitive tools for malaria during pregnancy are being worked from groups like the Foundation for Innovative Diagnostics (FIND).

New classes of antimalarial drugs to combat drug resistance will be forthcoming as a result of the efforts of Medicines for Malaria Venture and its partners.

There are often different data estimates regarding the malaria burden. The WHO and IMHE estimates do differ significantly on estimates for mortality. Do you think there is a role of APLMA in strengthening malaria data collection, diagnostic testing, surveillance, and vital registration?

Yes, these data do differ; we often find such differences in estimation in other disease areas as well. One key role for APLMA in strengthening all four areas mentioned (data collection, diagnostic testing, surveillance, and vital registration) is to find concrete, actionable ways to build sub-national capacity, district capacity in these functions.

Such capacity building, in my view, requires dedicated effort over 3-5 years to truly bear fruit. The result, however, will ultimately be better district-level data informing national programs and thus improving the validity of the data-sets used by international partners.

To eliminate malaria in 10 years, what research is most important to you?

First and foremost, operational research (OR) that builds capacity is the most important kind of research for me. Those working on the front lines at the District level need more research that can help them improve programs in the immediate and near term. While large scale research endeavors on implementation that require RCTs have an important place, they cannot deliver results within a relatively short time frame of 10 years.

Such OR that prioritises surveillance, aggregation, interpretation, and delivery of data for near term program monitoring and decision making on where to concentrate what efforts (LLIN, IRS, etc.) and how to allocate resources could be crucial to accelerate progress towards elimination. In terms of diagnostics, Ultrasensitive Rapid Diagnostics that are easy to use for community health workers and other front line health personnel are also important. Finally, products that can help reduce outdoor transmission will be another important area.

The Global Fund to Fight Malaria disburses money for medicines that have been pre-qualified by the WHO process. But many say the pre-qualification from WHO affects the medicine producers as the time it takes for pre-qualification is too long and it restricts competition and making effective drugs available to those who need it the most? In this context, should a drug approved by a national drug regulatory authority of affected countries not be considered for pre-qualification?

This is an important and challenging question. Ultimately, quality and safety have to be the guiding principles and pre-qualification assures that medicines meet a high standard of safety, efficacy, and quality. The process does take longer but my understanding is the WHO is trying to speed up this process. If we look at the other side, while there is a trade-off in time and cost, the risk of a drug being administered which may not show bio-equivalence (but purporting to do so) is harmful. There is a need for continued dialogue with WHO on how to speed up pre-qualification (and, in certain cases, make it more affordable) particularly, in cases where those who need it are being put at risk.

Last year public and private donors pledged the unprecedented US $14 billion to the Global Fund. What does this mean for the fight against malaria in Asia?

It’s important to breakdown the $14 billion figure. The Global Fund funds programs in TB, HIV and Health Systems Strengthening across the world. So, those funds are being spent for all thematic areas across all countries. The Fund is a source of resources for all malaria programs funneling 80 percent of all malaria resources globally.

A rough understanding based on the 2017-2019 allocation period is that roughly $375-400 million went to countries in Asia-Pacific; the vast majority of funds for malaria, rightfully go to Africa where the disease burden is the highest. That said, other funding mechanisms including domestic resources are on the rise, which is good. But we must continue to work to ensure we are complementing these funds and/or helping them transition to alternate, domestic sources, and budgets to reach elimination targets.

Resource challenges will persist, but we can continue to mobilise resources towards elimination by continued progress that inspires donors, partners, and local governments that these investments will save money in the long term by improving population health.

While India saw a drop in malaria cases between 2017 and 2018, it is still one of the worst-hit countries. According to you what are the major challenges for India to eliminate Malaria?

I see three challenges for malaria elimination in India. First is ensuring a more coherent and connected private and public sector response. There has been promising progress in other areas, such as TB, in connecting the private sector and public sector delivery through integrated notification systems and voucher mechanisms for diagnostics. In a similar manner, private providers, particularly at District levels, should be engaged in District-wide efforts around elimination and could be incentivised to do so through insurance reimbursement under the Health Reform, for example.

Second is devising better strategies and interventions to address urban malaria.

Third, ensuring that the political and public health leadership that produced the recent progress made in places like Odisha, particularly among rural and tribal populations does not backslide due to the slowing of momentum. The malaria effort in India, as elsewhere, requires sustained sub-national and national leadership; given the multiple competing priorities in health in a country of 1.3 billion, this is a challenge.

Yet, just as with the recent commitments on TB, the nation is poised to relentlessly pursue malaria elimination provided the right mentorship and support can be provided sub-nationally.

In recent years, we’ve seen a rise in the resistance level of ACT (artemisinin-based combination therapy) in South East Asian countries. How dangerous is it, if the resistance keeps going up?

This has been of considerable concern since the first reports of Plasmodium falciparum resistance to ACTs emerged around 2007 in the Greater Mekong. It’s important to remember that the battle against malaria history has been one with a long history of drug resistance. This is not to minimise the need to address drug-resistant malaria in GMS; monitoring it is critical. And we need to continually advocate and support efforts to develop new antimalarials as the parasite continues to evolve. This leads back to the central argument than an intensive push towards elimination in the region by 2030, and joining the bold goal of global eradication by 2050 is the best way to defeat malaria.

Add Comment